Bob Stuart is best known in the hi-fi scene as the co-founder and developer of Meridian Audio. For several years now, however, the Briton has been making a name for itself with the MQA audio codec. With this new format, Stuart wants nothing less than the digital music distribution to revolutionize the music industry. With the recent start of MQA streaming on TIDAL in Hires quality, he could already have succeeded.

Since the first presentation of MQA ( Master Quality Authenticated ) in 2014, discussions around the world have been booming. And as usual, when something new emerges in the world of high-quality sound reproduction, these discussions are unfortunately often characterized by prejudice, wild speculation and ignorance. At least the lack of knowledge is entirely excusable in this context, because MQA can hardly be explained, let alone understood, without profound knowledge of digital audio data and current developments in information theory.

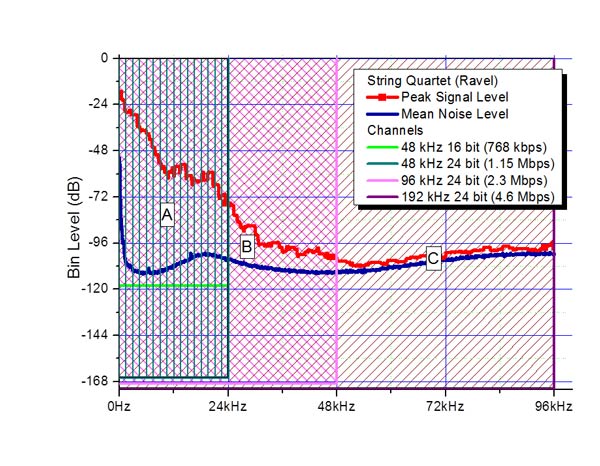

To put it simply, Stuart and his business partner Peter Craven see the current "hires" trend towards higher and higher sampling rates and resolutions as a negative development. It has long been a recognized fact that audio information beyond the previously postulated "hearing threshold" of 20 kHz definitely has an influence on the sound quality of a recording. That is why digital recordings with more than CD quality (44.1 kHz / 16 bit) make perfect sense ( a digital music file can reproduce sound frequencies up to the so-called Nyquist frequency, which corresponds to half the sampling frequency. 1 kHz can therefore map frequencies up to 22.5 kHz. ) According to Stuart and Craven, the actual information content that can be recorded with higher sampling frequencies is comparatively low, but it comes at the cost of an enormous increase in the data rate and thus the file size. In other words, a 96 kHz / 24 bit file is more than twice the size of the same CD-quality track, but it doesn’t offer twice as much audio information. This effect becomes even clearer when stepping from 96 kHz / 24 bit to 192 kHz / 24 bit. In turn, the file size doubles here, but the gain in information is only minimal. The vast majority of the additional data is (according to Stuart and Craven) wasted on digitizing silence and noise.

MQA is now taking a different approach. The codec focuses on the area where most of the music information is and preserves it perfectly. The additional information in higher frequency ranges is recorded in compressed form and hidden in the noise range of the lower frequencies, so to speak. This process, which Stuart describes as "music origami", can also be repeated: The information from a recording with 192 kHz / 24 bit is first "folded" into a file with 96 kHz / 24 bit, which is then again converted into 48 kHz / 24 bit is folded. The resulting file can finally be saved as a FLAC container and is only slightly larger than a conventional FLAC in CD quality (MQA speaks of approx. 20-30% additional file size), but much smaller than a hires file. This file can now be easily streamed or downloaded and played in CD quality on any conventional playback device. However, if the playback device is equipped with an MQA decoder, it can "unfold" the music origami it contains and play the recording in the original high-resolution master quality.

So much for the theory (in a really simplified form). Immediately after the MQA announcement, however, the first vehement discussions sparked, for example about the question of the extent to which MQA can actually be viewed as a "lossless" codec. And Bob Stuart presses has been formulating himself extremely eloquently since then in front around a direct answer to this question. While it still seems understandable that a large part of the information contained in the upper frequency range can be saved with reduced data without an actual loss of information, the question remains how and where this information is hidden in the resulting file. At least in relation to the pure digital data, information has to be lost somewhere. At Wikipedia , MQA is therefore also referred to as "lossy". However, Stuart insists that no music information is lost, only useless digitized noise, which can also be restored when the file is decoded using appropriate filtering.

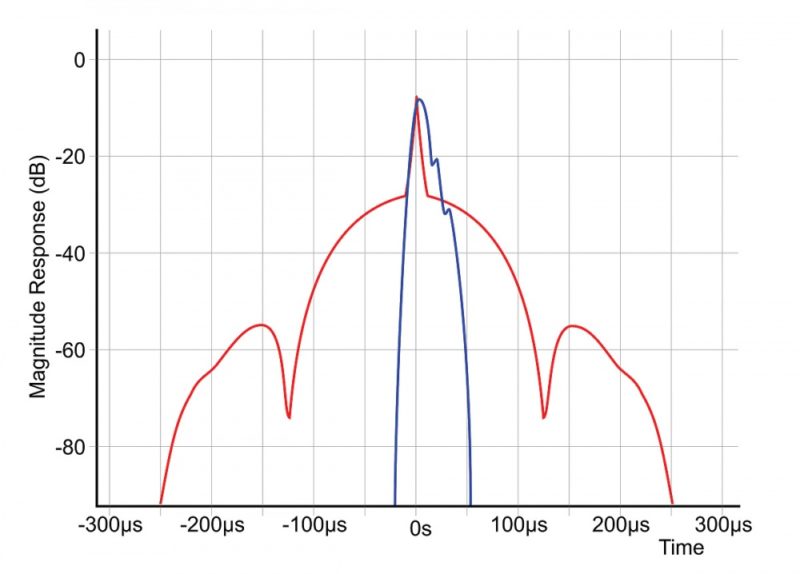

MQA, Bob Stuart and increasingly others even go one step further: An MQA-coded piece of music should sound better even when it is played on a device that is not MQA-compatible. Sounds amazing, but in fact it is not far-fetched, because this is where "authentication" in the name of Master Quality Authenticated comes into play. Because MQA does not see itself as a pure codec, but rather as a standard that encompasses all aspects of digital music distribution from recording to playback. By far the largest part of the digital music catalog available in streaming or download was created by digitizing original analog master tapes. Especially with older digitizations, but still to a certain extent today, the analog-digital converters used generate different degrees of scanning inaccuracies during this process. Again, in a very simplified way, you can imagine it something like this: Up to the Nyquist frequency already mentioned, a digital scan can actually perfectly map the different frequencies of a music signal. However, it is considerably more difficult to correctly represent the edges of the signal, i.e. the swing in and out of the tone, especially with high tones whose frequency is close to the Nyquist frequency. The filtering used in the A / D conversion generates a "slower" signal here, i.e. a signal with a lower edge steepness. In addition, artifacts, so-called ringing, arise on both the settling and the decay side. In particular, overshoots on the settling side can have a drastic effect on the subjectively perceived sound quality, as they never occur with a naturally occurring noise. Stuart and Craven summarize these effects under the term "time smear" (for example: "temporal smear"). In their view, any digital file based on a tape master is inevitably affected. However, the two inventors have recognized that these errors have a very typical signature for each A / D converter used, like a kind of fingerprint, and can therefore be corrected.

Bob Stuart is often quoted as saying that MQA is much more of a philosophy than a codec. And certainly nobody wants to deny the experienced tinkerer the love for music and its best possible reproduction. But it is also a fact that Stuart, Craven and their company MQA, Ltd. want to make money with this technology. In order to fully enjoy the MQA sound quality, you need at least an MQA certified D / A converter. And the manufacturers of MQA products should of course pay a license fee for each device sold, as well as music studios and streaming services that want to advertise their offerings with the improved sound quality. That probably also explains why prominent representatives of hi-fi manufacturers on the Internet and elsewhere are vocal get excited join the MQA discussion. Because apart from the license costs that an integration of MQA would entail in their devices, many fear an interference in the construction of these devices. MQA stipulates the use of certain chipsets to decode and authenticate MQA. What exactly happens in this chip, of course, only MQA knows, all other manufacturers could not have any influence on the current state of knowledge. In particular, companies such as PS Audio or Chord Electronics, which have previously relied on self-developed D / A converter algorithms based on freely programmable FPGA chips, would have to completely change their technical approach if MQA were to become an indispensable standard in the hi-fi world.

This is probably one of the reasons why the list of partner manufacturers at MQA is still rather manageable. But in addition to - not surprisingly - Meridian, there are already some big names here with Pioneer, Onkyo, Technics and NAD, as well as smaller specialist providers such as Mytek, Aurender or Brinkmann. The name Bluesound also appears in this list, and due to the latest developments, this multiroom offshoot from NAD has a very special position in the market. Until recently, as usual with the introduction of a new standard, the very limited amount of MQA music available was one of the main arguments of the critics. There has been a framework agreement with Warner Music for some time, and the corresponding music is available for purchase on download portals such as HighResAudio.com or Onkyo Music . However, by and large, the music industry a few hundred audiophile albums are nothing more than footnotes. But since the beginning of January the MQA world has been very different.

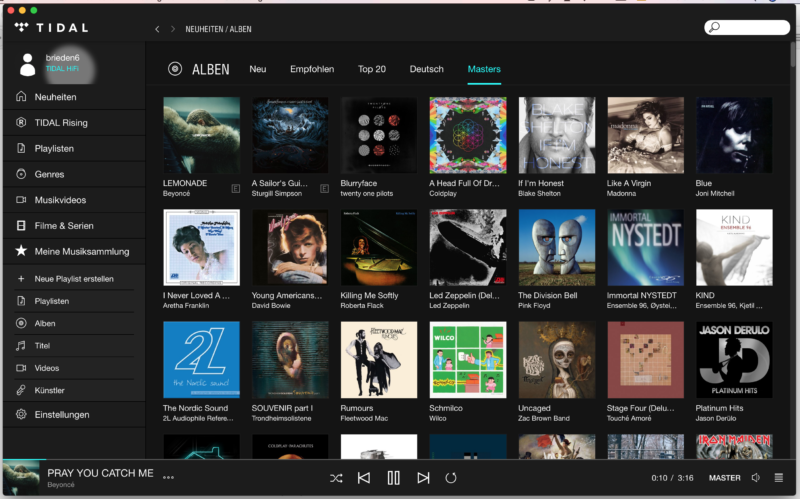

Just in time for the start of the CES, the long-announced collaboration between MQA and the streaming service Tidal was finally launched. All subscribers to the "HiFi" premium offer from Tidal can now enjoy the ability to stream selected albums in the original master quality. The offer is currently still rather limited, but at least numerous classics from pop and rock history as well as current material from popular artists such as Beyoncé or Coldplay are available at any time. There is little doubt that streaming is the future of the music industry as a whole. But for real hi-fi fans looking for the best possible sound quality, high-resolution downloads were still the method of choice in the digital sector. But if MQA also delivers the promised quality in streaming and Tidal lives up to its announcement to offer all new albums in MQA with immediate effect, there is now at least an interesting alternative.

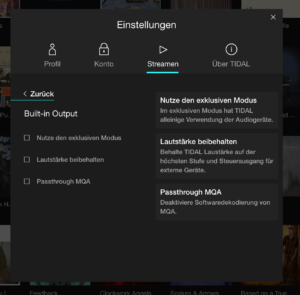

However, there is still one small restriction, and this is where bluesound comes into play again. Currently, Tidal's MQA support is limited to the desktop versions of the Tidal software for Windows and Mac. Mobile players and other systems are initially left out. All other systems? No, not quite, because a brave British-Canadian manufacturer of high-quality multiroom systems has done its homework and was able to offer a playback option on Tidal at the start of MQA that does not rely on a computer. All Bluesound products, including the apps for iOS and Android used for control, can already play Tidal MQA streams in full master tape quality. This includes, for example, the Bluesound Node 2 , which is simply connected to the existing hi-fi system, making every system MQA-compatible.