Text: Olaf Adam; Photos: Shutterstock, Wikimedia Commons

This article originally appeared in 0dB - The Magazine of Passion N ° 3

Rock 'n' Roll or Beethoven? Picasso or Hopper? Cozy Sunday on the sofa or an alpine hike? We perceive different things as beautiful. But is there such a thing as "True Beauty"?

First of all: on the following pages you will certainly not find a definitive answer to the question posed in the introduction. The great minds of world history have already racked their brains about the nature of beauty without coming to a generally applicable answer.

Plato, for example, assumed that true beauty, the “beautiful in itself”, actually exists, namely as a kind of archetype of the beautiful, as a pure, perfect and unchangeable metaphysical reality. According to his imagination, this eludes human perception, but can be grasped spiritually. Things that humans can grasp with their senses, however, have at most a relative beauty - they are only beautiful partially or in a certain respect. Their beauty isn't absolute – it can be overshadowed by something more beautiful or be lost over time.

More than 2000 years later, Goethe agrees with the Greek thinker: “The beautiful is a manifestation of secret natural laws that would have remained hidden from us forever without its appearance.” So is it actually the case that there is a “true beauty” that we humans recognize sometimes more sometimes less? It doesn't seem that easy after all. Goethe's contemporary Schiller, at least, did not necessarily locate the feeling of beauty in the ratio: "Truth is there for the wise, beauty only for a feeling heart."

If you enter “beauty” in an Internet search engine today, the results displayed mainly consist of cosmetic tips and women's faces. Obviously, at some point our society decided to refer the term primarily to the appearance of people. There must be reasons for this, so maybe we will find answers to the question “What is beautiful?” First of all, beauty in this context is inevitably a construct shaped by time, culture and the respective living conditions.

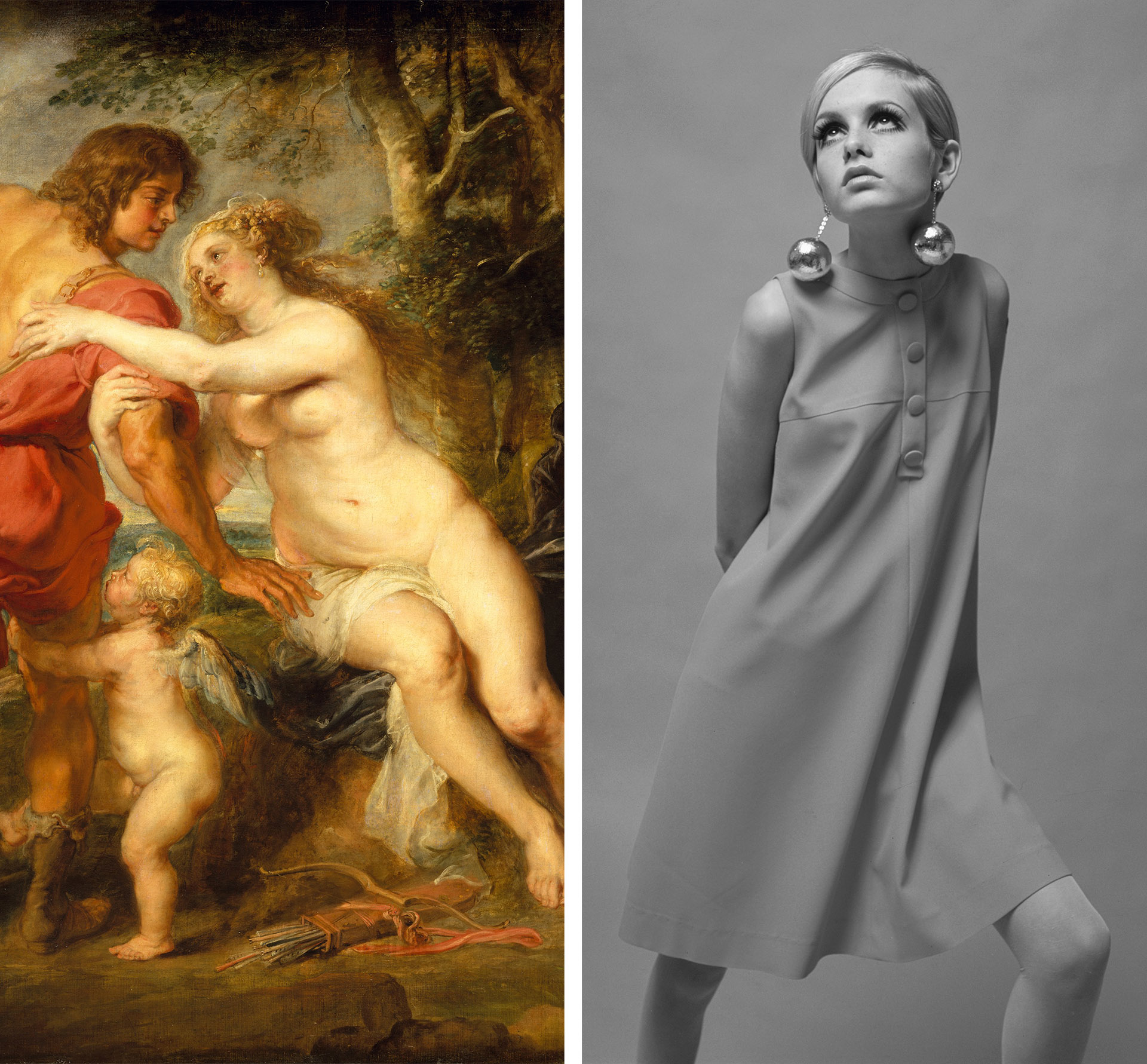

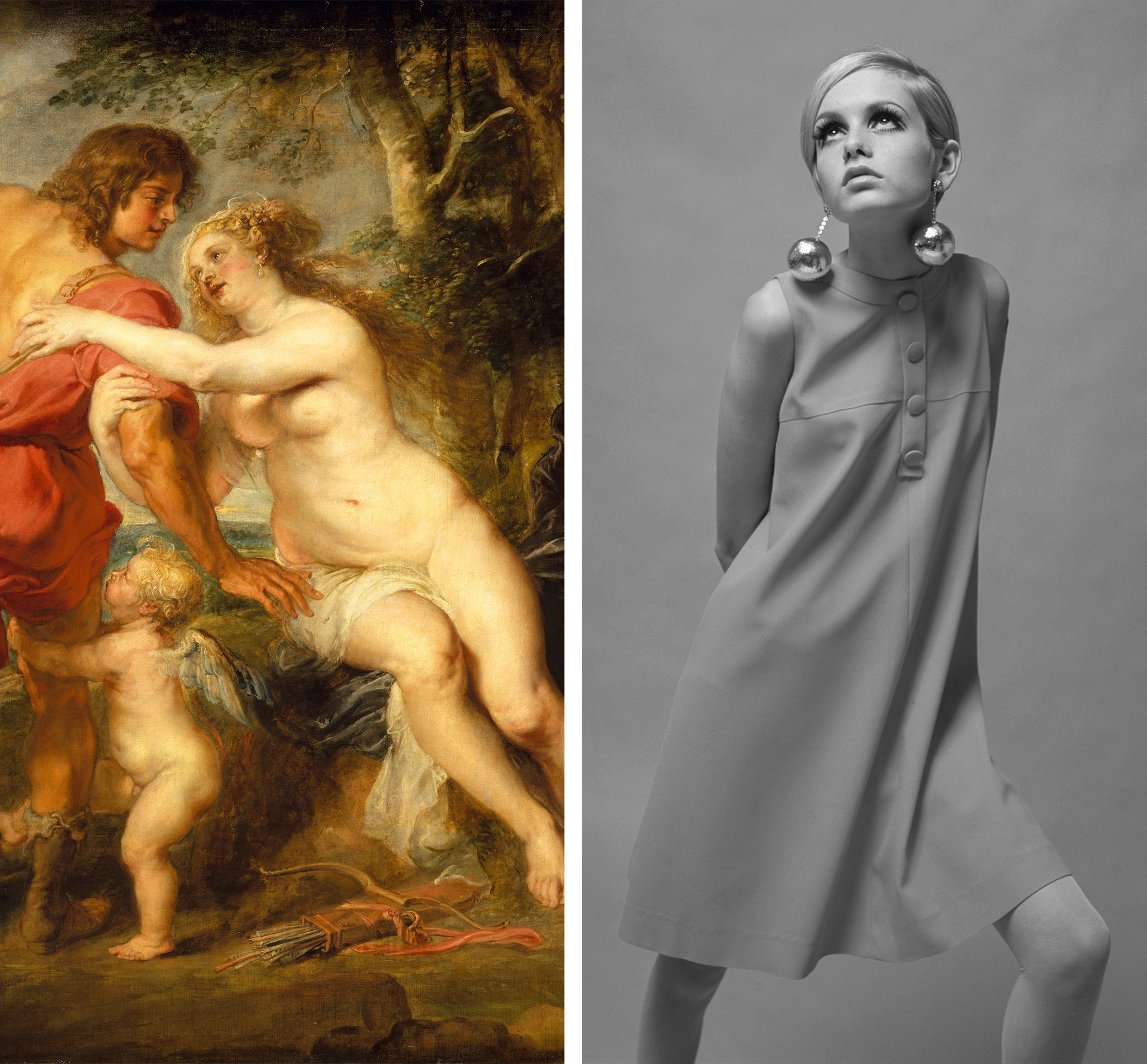

Just take the so-called ideals of beauty in the changing times. There are worlds between Rubens' well-proportioned female bodies in the 16th century and Twiggy fashion in the swinging sixties of the last century. But do such ideals have anything to do with true beauty? Hardly likely. Rather, it is about the idea, created by a society and spread by the respective media of the time, of how people should please look.

And since the world is the way it is, such “ideals of beauty” have almost exclusively related to women over the years. Or should one say that they were directed against them? In view of the numerous illnesses, impairments and mutilations that women in different cultures had to endure and still suffer today in order to correspond to a certain “beauty” ideal, this reading is formally imposing. In any case, men could almost always and almost anywhere look how they wanted, as long as they could still squeeze into the clothing prescribed by the respective fashion trend.

Such comparisons are therefore almost certainly unsuitable for the search for true beauty. And yet it remains undisputed that we perceive some people as beautiful, while others less so. This is especially true for faces, and here symmetry seems to play an important role, regardless of the prevailing cultural character.

Most science assumes that we find people attractive who appear healthy and that therefore a symmetrical face shape, even skin and other indications of physical health are perceived as beautiful.

From the point of view of evolutionary biology, there may be something to it, but this representation is not completely conclusive either. Because studies with artificially generated portraits have shown that a face can also be too perfect. If you let a computer generate the mathematically ideal face, then the result apparently lacks the necessary dose of reality, a small sympathetic deviation from the ideal that turns a beautiful picture into an attractive person. When it comes to interpersonal relationships, you have to distinguish between beauty and attractiveness. The latter is too strongly influenced by our culture, our preferences and our hormones to allow a reliable statement about the former.

So let's withdraw for a moment from the mixture of human sensations, cultural phenomena and biological processes and look for evidence of the existence of true beauty in more tangible areas. Indeed, there seem to be some mathematical principles of beauty but the depths of their meaning are not yet fully understood.

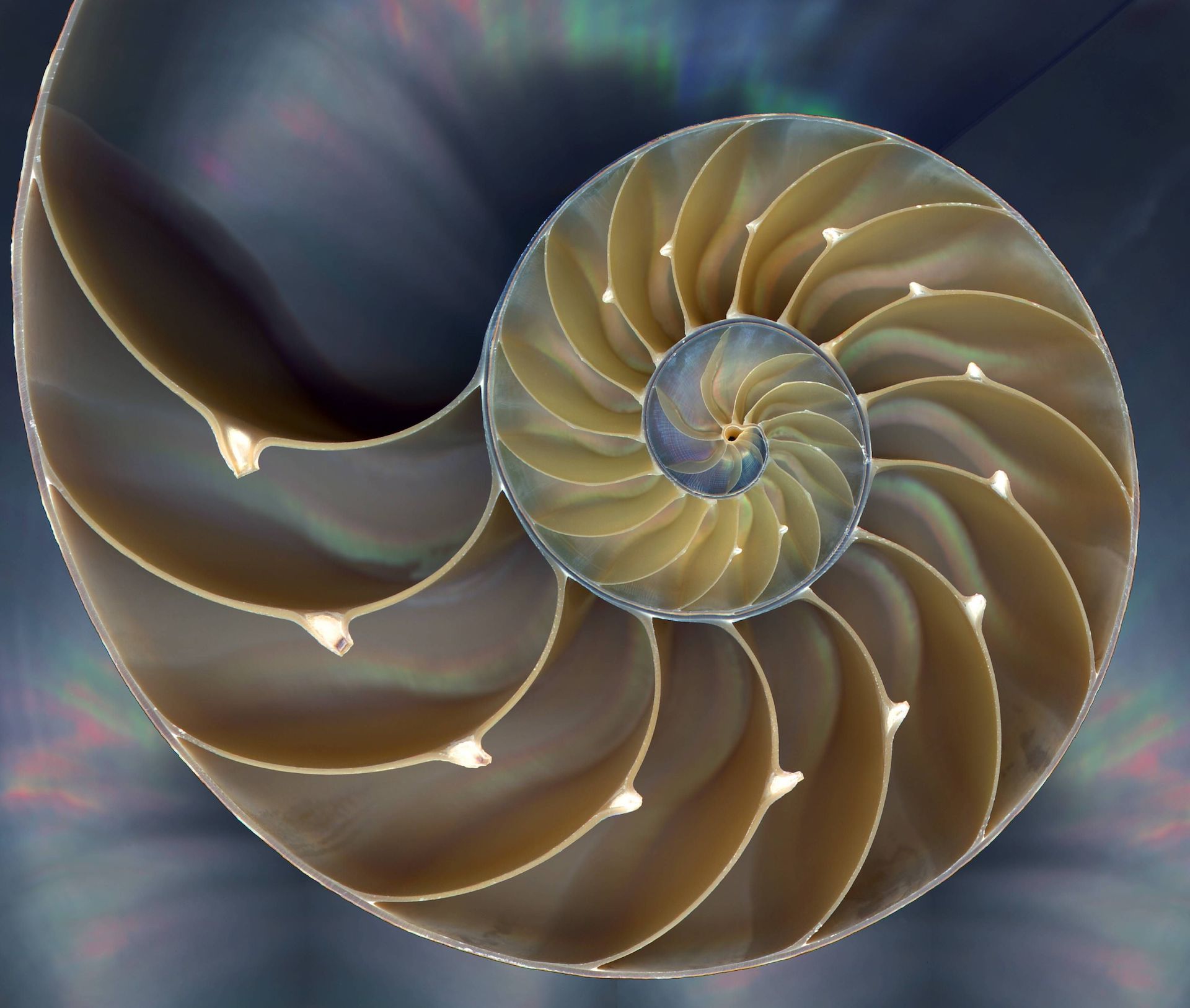

The best-known example of this is probably the golden ratio. Coined as a term in the middle of the 19th century, the mathematical basis for it was already known to Euclid (around 300 BC). We speak of the golden ratio when a route (or other size) is divided in such a way that the ratio of the total route to the larger part corresponds to the ratio of the larger part to the smaller. The division ratio described in this way, the golden number, is an irrational number with an infinite number of digits after the decimal point, but corresponds to approximately 1.62 or a division of approx. 61.8% for the larger to approx. 38.2% for the smaller part. All of this sounds very abstract to non-mathematicians, but we encounter the golden ratio and the golden number every day without even realizing it.

It has been proven that we perceive the proportions resulting from this principle as particularly harmonious and beautiful. And that's why it has been used for centuries in art, architecture and in the design of everyday objects. One could of course assume a cultural influence here as well and assume that we would have “learned” over time that such proportions are beautiful.

But there actually seems to be more to it, because amazingly, the golden ratio is also found in nature. The arrangement of the leaves of many plants around the central axis follows this relationship; spruce cones, inflorescences of sunflowers and shell shells are arranged in so-called Fibonacci spirals, which are mathematically based on the golden ratio. The golden number has also been identified as a decisive variable in crystal structures, resonances of planetary orbits and even in certain aspects of black holes.

So can beauty be reduced to this one number, does it follow a cosmic law? Unfortunately not, or at least not exclusively. There are numerous examples in nature and in art that are beautiful even without the influence of the golden ratio. Not all plants follow his rules, and in music, if at all, other mathematical aspects are more relevant.

In the performing arts today, classical beauty is often understood as a kind of superficial ornament, while “real” art should provoke emotions, stimulate thought or comment on society. Beauty is of secondary importance, maybe even a hindrance, and the works created against this background even appear extremely ugly to many. Others, however, find them beautiful and like to look at them. Many aspects of beauty are beyond the scope of mathematics and theory anyway. How do you want to put the breathtaking beauty of an Alpine panorama in numbers or the moment when your own child takes the first steps? Can you measure how beautiful a tender touch is, or does the objective beauty of a sunset actually increase when viewed with a loved one?

Hardly, because every theory of the beautiful has little, often nothing at all, to do with real life. No matter what psychology, mathematics, social science or aesthetics say, in the end the following applies: What pleases is beautiful.