Text: Andreas Günther; Photos: Photocase, Shutterstock

This article originally appeared in 0dB - The Magazine of Passion N ° 3

Why do minor keys make us sad, why do we rejoice in music that uses a major scale? Because an ancient Greek overheard the planets on their orbits. Bach and the Beatles followed these mathematical rules of the music game.

Pythagoras. Many math students still shudder at this name. The great Greek philosopher not only founded today's mathematics, he is also the creator of our musical culture. Pythagoras lived around 500 BC, had spent a few years in Egypt and studied numerical mysticism there. In his view, people are ruled by gods, numbers and proportions. Mortals attain the highest form of spiritual approach to the gods - through music. Which embraces the entire universe.

A wonderful idea: the planets circle through space and produce sounds in the process. Inaudible to human beings, the purest music of the gods - but which can be translated by and for mortals. Two terms from this philosophy have made it into our linguistic usage today: The individual tones of the “music of the spheres” result in a magical harmony, the “symphonia”. From today's perspective, the worldview of the ancient Greeks also had misleading moments. One can still understand that the school around Pythagoras assumed that fast planets produce loud noises and that the pitch arises from the proximity or the distance to the center of the universe. However, the fact that this center of space is supposed to be the small planet earth, of all things, makes us smile today. Which doesn't change the fascination of the music of the spheres.

Even the enlightened, knowledgeable Goethe stuck to this poetic idea 2000 years later. He opens his famous “Faust” with a “Prologue in Heaven” and has the Archangel Raphael proclaim: “The sun sounds in the old fashion / in brotherly spheres of contest, / and its prescribed journey / completes it with a thunderous walk.” Pythagoras tried exactly this: To grasp the sun in tones, a translation of the star sounds into resounding mathematics. To do this, he built the instrument of the instruments: a "monochord". The "instrument" with one string was used according to mathematical guidelines. The Pythagorean system still works today. If you split a string exactly in the middle, you get the octave of the base note, an oscillation ratio of 1:2. Pythagoras divided the string into a total of twelve units - which represent our system of twelve semitones still today. Eight defined tones on this system - played one after the other - result in a scale. Three defined notes - struck at the same time – form a trichord that determines the harmony. The middle tone is characteristic of this trichord for our ears: the third. A “major third” is defined as bright, wide and open - the key type “major”. A “minor third”, on the other hand, sounds sad, dramatic to us - the pitch type “minor”.

"Major" and "minor" are term that would not mean anything to their inventor Pythagoras. Because the western musical reality has simply forgotten several other keys over the centuries. Today hardly anyone plays “Lydian”, “Phrygian” or “Dorian”. In a critical sense, our tonal system is impoverished - the two poles major and minor determine a world that was richer, but also more unfathomable, even in Plato's time. For Plato music was not only beautiful but also dangerous. The philosopher called for state supervision. Since music can arouse “wild delight”, democracy must be protected against intoxicating uprisings. Years and centuries later, moral apostles raised the same outcry because of Berlioz, Wagner, Elvis or the Beatles.

The noble Greeks were particularly contemptuous of the "Phrygian fashion". Here orgiastic music with flute, clapper and hand timpani raged - especially among the lower social classes. The pop music of antiquity. If Plato had had his way, educated Greeks would only have heard Dorian. This key made people "stronger against fate", could create inner balance, Doric was considered chivalrous and manly. Lydian, on the other hand, was considered more feminine: the key of delicacy and intimacy.

Aristotle demanded it as the standard for educating the young. In his "Politeia," Plato disagrees: "...we have no need of lamentations and lamentations, for which reason the Lydian keys must be eliminated; for they are useless for women who are to be valiant, much less for men." Likewise, the "mushy keys and those suitable for drinking parties" - including the Ionian minor key - were to be despised. In retrospect, this is a difficult philosophy to understand - after all, the Lydian is similar to the modern major, which for us proclaims verve, strength and joy.

Hearing is cultural enslavement. We are more than 2000 years away from the diversity of the ancient keys. Today's ears are conditioned to major and minor keys, at least in Western culture. We are at home in this system, but also trapped in it. This poverty is homemade. Even in the Middle Ages, monks sang in up to eight different modes plus minor modes. God was praised in Doric, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Ionian, Aeolian, Locrian. Some tonal families have survived in the niche of evangelical and ecumenical hymnals. Bach (1685 - 1750) still knew how to compose in Dorian, even Beethoven (1770 - 1827) was tempted to compose a string quartet in Lydian key (Opus 132, 3rd movement, F major with b instead of b).

New and foreign systems arouse rejection, not infrequently even fear. In the 20th century, Arnold Schönberg (1874 - 1951) wanted to free concertgoers from the captivity of major and minor and lead them into the promised land of twelve tones. The success of the "Dodecafonie" remains limited to this day. Even sadder was the revolution of some instrument makers, who constructed pianos with quarter tone intervals - shopkeepers of music history. Pythagoras remains the shaper, but also the dictator of our sense of hearing.

Only in one point the doctrinal edifice of Pythagoras is lagging. All students, who are tormented by the theorem of Pythagoras, should ask their teacher sometime about the "comma of Pythagoras". Very few teachers will be able to explain the phenomenon without stammering. The problem is fascinatingly beautiful: The music of Pythagoras is the likeness of the solar system - one confirms each other. The perfection of the doctrinal building works even to the smallest unevenness. For example, the year can only be divided into 365 days with a certain difficulty - every four years, a leap day has to be added to February.

Fascinating equivalence in the musical system: Here, too, corrections are necessary - if you build twelve Pythagorean fifths and compare them with the tone that, in mathematical terms, should be reached by seven octaves, you discover a difference - the "Pythagorean decimal point". For the very meticulous mathematicians among our readers: seven octaves correspond to a frequency ratio of 1:128 - twelve fifths, on the other hand, correspond to a ratio of 1:129.746337890625. A tiny difference, which, however, drove the following generation of musicians to the edge of compositional freedom. For especially with fixed-tuned keyboard instruments, harmonic fantasies had to be avoided; the tiny difference could build up in distant keys to grating discords. Which is why, 2200 years after Pythagoras, various musicians were tinkering with a new form of the musical scale. Again, it's a game of arithmetic. Around 1700, Andreas Werckmeister distributed the delicate irregularities of the Pythagorean comma over all semitones - the "equal temperament" was born. A small step for an instrument maker, a big step for music history - since Werckmeister, no instrument sounds "pure" according to Pythagoras. The famous "Das Wohltemperirte Clavier" by Johann Sebastian Bach is a direct response to the new possibilities - a universe of preludes and fugues that reaches into remote keys. The Starship Enterprise of all piano literature, in a manner of speaking

Most people follow the rules of major and minor? Not quite: The Chinese have little use for "our" music. In the Middle Kingdom, music sounds according to the dominant rules of the pentatonic scale. Instead of seven tones, the tone "alphabet" in East Asia knows only five. In Arabic music, the octave is divided into 24 intervals of equal size. The three-quarter tone is identified by musicologists as a core feature. It is difficult to comprehend for Western ears. Indian classical music impresses with the aura of the small and subtle. In essence, only one instrument is allowed to play the melody part. Another harmony instrument is charged with drone notes - unchanging continuous tones. These are joined by one or two rhythm musicians with percussion instruments. The range within an octave knows 66 microtonal steps, in practice 22 steps are used.

Again, we are but slaves to our culture. In Western music, we owe the basis to the work of Pythagoras. A fascinating idea: Beethoven, Bach, the Beatles and James Last composed according to the same rules formulated by a Greek philosopher while maltreating a wooden box with a dried goat intestine stuck to it.

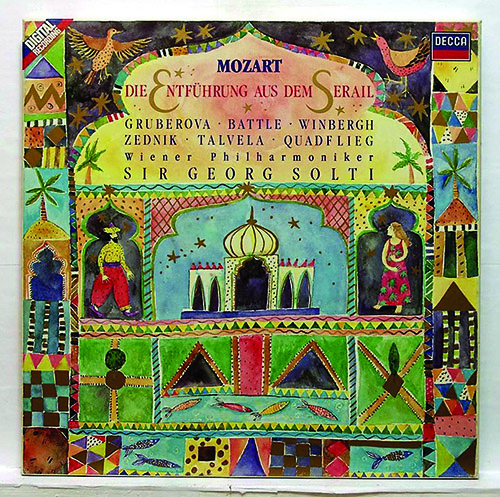

MOZART - The Abduction from the Seraglio

In Vienna in 1782, this opera was not only considered chic, it was downright revolutionary. Mozart leads the audience into a harem (!) And researches the musical language of the Turks - including a choir of the "Janissaries", the elite soldiers of the Turkish Empire.

Top recording:

Edita Gruberova, Gösta Winbergh - Sir Georg Solti (Decca)

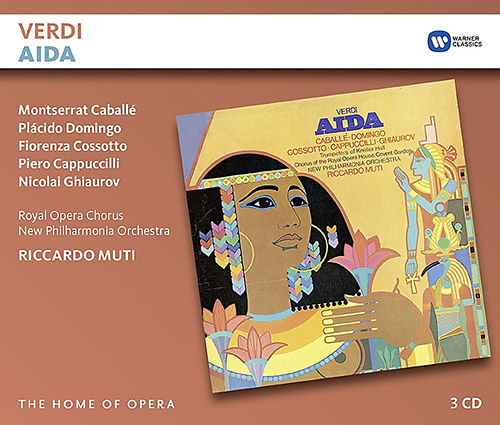

VERDI - Aida

Giuseppe Verdi carried out serious research: How would the music have sounded in ancient Egypt? He found wonderfully shimmering, strangely beautiful tones. His most famous idea is used and abused at every football game today: the triumphal march sounds from a specially developed one

ten fanfare trumpet - designed by Adolphe Sax, the inventor of the saxophone.

Top recording:

Montserrat Caballe ?, Placido Domingo - Riccardo Muti (EMI)

MAHLER - The song of the earth

A music between intoxication and sadness - with strong echoes of what western ears associate with “Chinese”. Gustav Mahler set six poems by ancient Chinese poets to music. Great symphony, highly emotional, fascinatingly orchestrated and a festival of sound on good speakers.

Top recording:

Fritz Wunderlich, Christa Ludwig - Otto Klemperer (EMI)