by Olaf Adam

It started with Napster and Deezer, Spotify made it increasingly popular, and the spectacular launches of Tidal and Apple Music have finally dragged the subject into the mainstream light: streaming music is a huge thing, and for many no less than the future of Music distribution. But at the same time the shouting is great. Many musicians complain about the low income from streaming and quote amounts in the hundredths of a cent range per stream. And spurred on by the fast-moving sub-culture of social media, this accusation is being ruminated a thousand times and is now considered a fact for many. There is talk of exploitation of artists, even of modern digital slavery. The culprits are - logically - the stingy streaming services and their customers who support this mess a million times over. Questioning? Unnecessary. Make yourself smart? Much too exhausting! It would actually be relatively easy to break down this conceptual construct in a few steps. And that is exactly what the Berklee Institute of Creative Entrepreneurship recently did in the RETHINK MUSIC study . Let's start at the beginning:

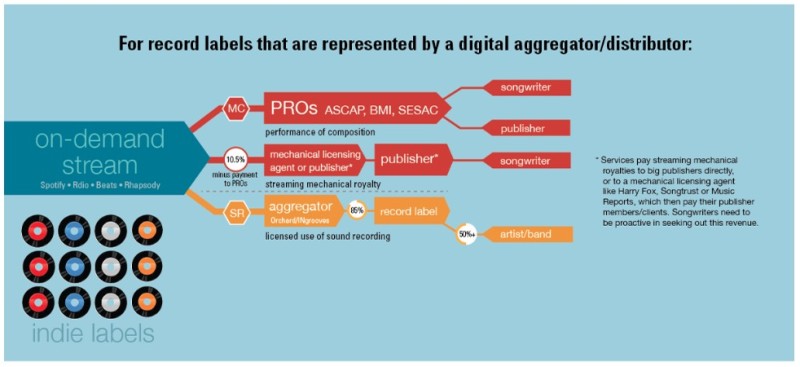

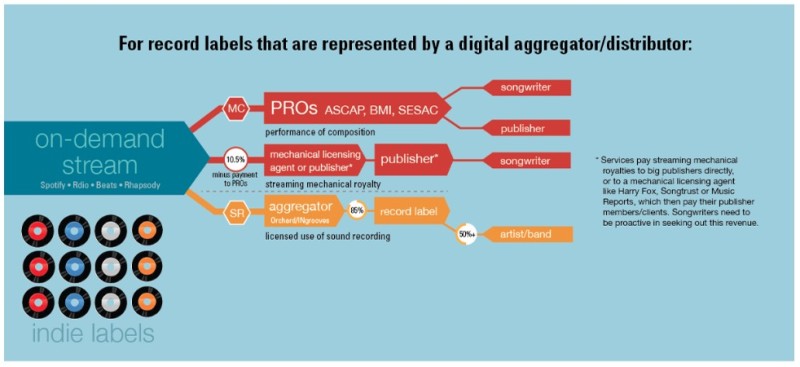

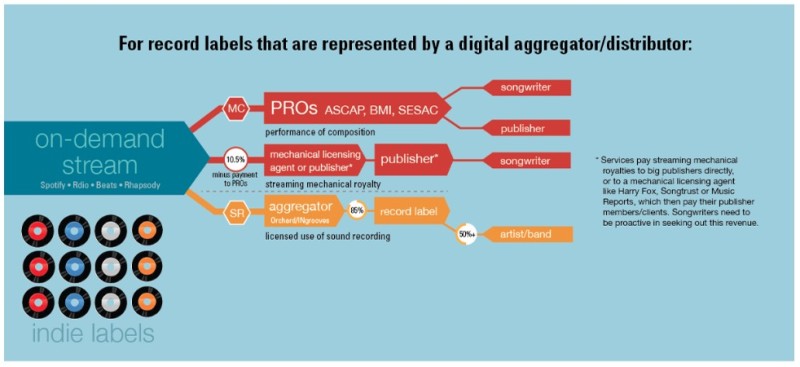

The artists? Yes, if they are called Madonna, Jay-Z or Beyoncé and have extensive rights to their own songs. For 99% of musicians worldwide, however, this should not apply. Because they have assigned the exploitation rights to their labels, i.e. the music companies. To do this, they have signed contracts in which it is precisely regulated what proportion of the income they receive themselves. The streaming services have nothing to do with this, they simply pay their distributions to the labels.

Uh ... no. Companies certainly want to earn money from streaming, and that is their right. In return, they keep a certain share of the income from advertising and subscriptions, the rest is distributed depending on the number of views. At around 30%, this proportion is in no way outrageous, because that is pretty much what it keeps for itself in the case of an iTunes sale, for example. And the streaming providers themselves would probably confirm that this proportion is rather low, because so far none of them has apparently ever been in the black, as all sales are currently being invested in marketing and the expansion of the technical infrastructure. Around 70% of the streaming income therefore goes to the rights holders of the works. And in most cases these are the labels.

That is certainly to a certain extent a question of the self-regulation of markets and also a matter of opinion. It is true that there have always been some people who enjoyed spending a lot of money on music. But there have always been many more people who were just not ready for it. And this development reached its sad climax in the late 1990s and early 2000s when millions of illegally exchanged MP3s actually damaged the music market extremely and plunged the industry into a deep crisis. One shouldn't forget, however, that music sales have been rising again around the world for several years. And that is in large part due to the growing streaming business. You just have to be realistic when considering this situation. For a dedicated hi-fi fan, it is certainly nothing special to spend 30, 40 or more euros on music every month. And no one is stopping him from continuing to do so. However, this willingness has not existed for a long time in the general population. And this trend was only reversed with streaming services. On average, a subscriber to Tidal, Spotify and Co pays around 120 euros per year. Each year. That's a lot of money, and certainly more than many customers spent on music just a few years ago. The rising income of the music industry is evidence of this positive development.

That's true, unfortunately. But it's not the bad, bad streaming services to blame, but the labels. And to a certain extent, that must also be said, the artists themselves; after all, they signed their contracts themselves. However, the behavior of many (all?) Labels borders on insolence. Because the artists only receive their contractually agreed share of the direct streaming income. However, the labels earn money on other levels when it comes to streaming. For example, there is often a kind of basic fee that streaming providers pay to labels so that they can make their catalog available at all. It is unclear whether and in what way the individual artists will participate in this income. Some labels have also secured company shares in various streaming services and, in return, have agreed to discounted payouts per title played. The bottom line is that in these cases the labels earn twice, but only have to share a much smaller part with the artist.

Well, dear Taylor Swift, dear chatterboxes and finger pointers. Not everything in life is simple enough to fit into a 140-character tweet. And simple answers to complex topics are often dangerous. If you really want to try that with this topic, it can only be like this: It is not the streaming services that exploit the artists, but the labels. (Thanks to John Darko from digitalaudioreview.net for bringing the above-mentioned study to our attention.)